Released: March 23, 1998, EMI/CMC International

“Time will flow, and I will follow”

The Context

Steve Harris swore up and down that The X Factor was one of the best albums Iron Maiden ever released. The problem was that virtually nobody else agreed, and although the record made the Top 10 in the UK and the supporting “X Factour” played respectable venues throughout Europe, most audiences were little more than accepting at best. And the introduction of Blaze Bayley as frontman was a complete nonstarter in America, where the band was reduced to a club act and played smaller venues than when they first came to the country with Paul Di’Anno in 1981. To be fair, they were signed to an indie label (CMC International) with no promotional muscle in the US, and The X Factor came out during a time when heavy metal as a genre was box office poison, so they weren’t set up for success. However, nobody other than Maiden’s founding bassist actually believed that the band was anywhere near their peak.

But as famously hardheaded as Harris was known for being, it was clear that he and the band (or at the very least, their legendary- and also famously hardheaded- manager Rod Smallwood) had taken in some of the criticism directed at the overly grim X Factor. Just a year later, Maiden put out their first proper compilation in the form of Best of the Beast and underwent a massive reissue campaign for their back catalogue. This was at least partly intended to restore some goodwill, but at the same time there was some doubling down, as not only did Best of the Beast run in reverse chronological order and open with 4 songs featuring Bayley at the mic, but it even began with a new track called “Virus” that tried to have it both ways: the track was more melodic and a bit brighter than The X Factor, but its bitter lyrics were very clearly aimed at critics and disgruntled fans. But while Best of the Beast and the “Virus” single both charted reasonably well in the UK, neither really endeared fans to this new iteration of Iron Maiden or to Bayley himself, who (mostly unfairly) took most of the blame for the group’s dwindling fortunes.

And of course, lurking in the ether was Bruce Dickinson. For a moment it looked like Maiden had the upper hand: while 1996’s Skunkworks was an underrated gem (a topic for another article, perhaps), it was also an unmitigated commercial disaster that nearly bankrupted the singer. But Dickinson was much better at reading the room, so when Roy Z. reached out about making a heavy metal album, he retreated to Los Angeles and managed to convince Adrian Smith (who was also beginning to dip his toes back into music after years in the wilderness) to come along. In pretty quick succession Bruce put out two albums that, while not huge sellers, were at least liked by the metal community. Dickinson may not have had the sales, but he had the respect of his audience and critics, and that went a long way towards making Maiden look even more out of touch and long in the tooth.

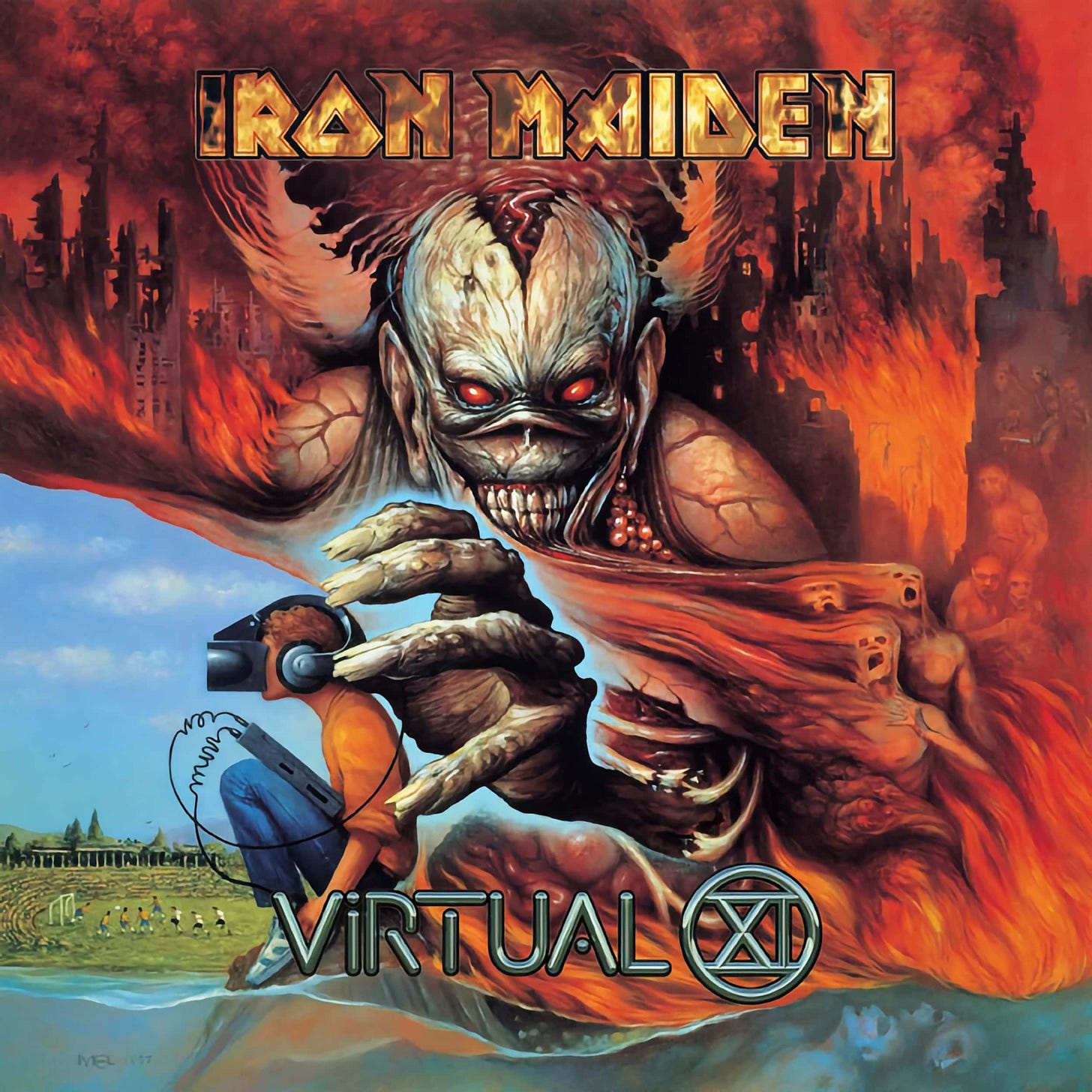

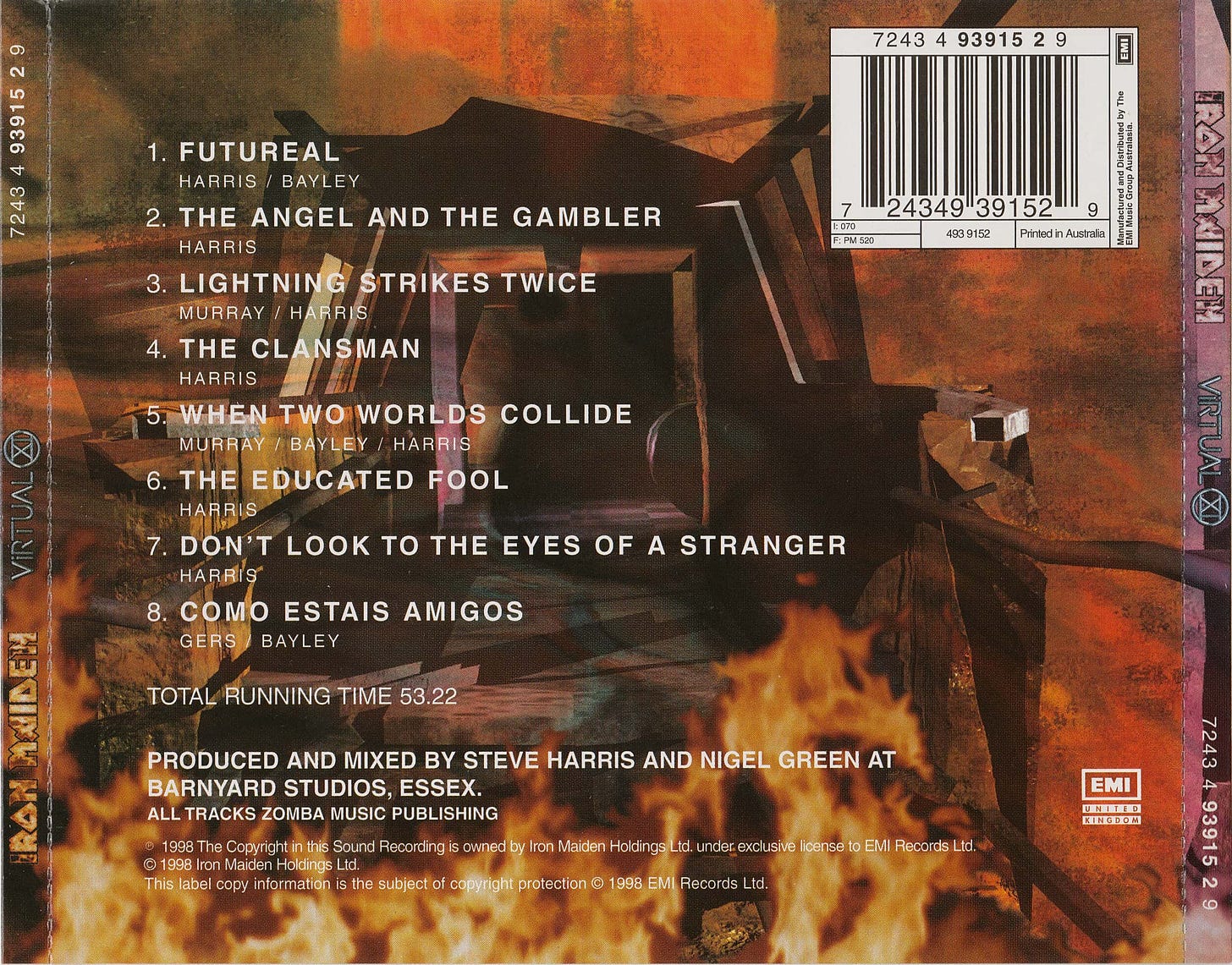

Nonetheless, Harris persisted. And it is not at all incidental that Harris is the only member mentioned thus far: it wasn’t just that he had always been Maiden’s creative driving force, but without Smith or Dickinson as either foils or co-captains, the bassist was left alone to make almost all of the decisions. And so he marched forward to make Iron Maiden’s eleventh album, in his mind making some concessions by limiting the tracklisting to 8 songs (deliberately recalling their ‘80s classics) and aiming for a brighter and theoretically catchier sound. At the same time, Blaze Bayley was much higher in the mix and front and center throughout, making it clear that nobody was giving up just yet.

The (Original) Reception

The X Factor wasn’t a hit, but it had its defenders- every so often there will be someone online swearing that it’s Maiden’s most “mature” album or something like that. However, Virtual XI was a straight-up flop that received overwhelmingly negative reviews and was lambasted for everything from its cheesy cover art to the disastrous 9-minute lead single “The Angel and the Gambler” to the fact that Blaze Bayley was a person who existed. In the UK, where the band had been a chart presence since their very first single, Virtual XI became their first studio album in 17 years to not reach the Top 10, and neither “The Angel and the Gambler” or “Futureal” did any business as singles- the former made the Top 20, but that was just the diehards showing up for a week.

Touring didn’t help: the shows got even smaller, and while the band did fine with the newer material, Blaze was comically unable to handle anything recorded before he joined the group. And not only did the internet spread the word- calling out an especially horrendous take on “The Trooper” in particular- but even Nicko McBrain found it increasingly difficult to hide his frustration with the state of affairs, barely working up the nerve to defend Bayley in interviews and occasionally being caught up tape bagging on his singer’s stage presence. And when the US tour, which had incredibly poor advance sales, ended up getting cancelled on account of illness, it was clear to everyone that the band couldn’t continue carrying on like this, and even Steve Harris couldn’t deny that business was seriously suffering.

That didn’t mean that Harris was quite ready to give up: he had already begun writing a handful of songs for the next album, and was fully committed to recording them with Blaze. Rumor was an emergency band meeting with Rod Smallwood finally convinced Harris that a drastic change of course was necessary, so Blaze Bayley was let go and a frantic call was placed to Doogie White, who had previously auditioned for Maiden after Bruce left. But White had carved out a decent journeyman career for himself in the ensuing years and no longer felt comfortable singing traditional heavy metal, so once again Maiden was left without a singer or options. But as Smallwood first softly and then loudly reminded Harris, there actually was another option…

How Does It Hold Up?

Absolutely nobody (not even the band) will argue that Virtual XI was a masterpiece, or even a great album, but was it really that bad?

Actually, it really wasn’t, and in several key moments it was quite good. To begin, Harris’ production, while still too thin and given to a clanging drum sound, was light years better than the muddy recording on The X Factor. The guitars were weightier and more dynamic, and Blaze didn’t sound like he was fighting to be heard over laughably obtrusive bass lines. And the songs were stronger as well: “Futureal” was an energetic and stirring opening racer with lively, fully committed and locked-in performances from the entire band, and deserved a better fate as a single since it truly was the strongest thing Maiden had released in several years.

Although nothing else on Virtual XI was as robust and fleet as “Futureal”, in hindsight there were more than a few dark horse charmers- in some respects this was more a record driven by deep cuts as opposed to the usual mix of anthems and interwoven album tracks. This was perhaps most evident in the presence of two Dave Murray co-writes, both of which were moody, haunting and melodic minor gems, but there was also Harris’ “The Educated Fool”, which was thoughtful and actually mature in a way that The X Factor’s clunky lyrics only tried to be. And speaking of thoughtful and mature, the closing Blaze Bayley/Janick Gers number “Como Estais Amigos” may have ended Virtual XI on a major down note, but it was empathic in its depiction of the Falklands conflict and felt earned in its sorrow.

But at the same time Steve Harris couldn’t get out of his own way, and when Virtual XI misstepped the results were almost comically disastrous. Everything about “The Angel and the Gambler” was inexplicable and inexcusable: it was one thing that Harris wanted to craft a lighthearted tribute to ‘70s UFO, but did he have to insist on playing keyboards himself? And making them sound so dinky? And placing them so high in the mix? And extending the song to an excruciating 9 minutes? And stopping everything dead in its tracks in the middle for a pointless and never-ending interlude? And barely bothering to write any music for said interlude? And insisting on releasing this as the first single???? From inception to completion, “The Angel and the Gambler” was the single worst decision Iron Maiden ever made, and not even getting around to releasing a streamlined 3-minute version for the video (after first trying to whittle it down to 6 minutes) could undo the ill will- putting this out as the teaser for Virtual XI created a stench the album couldn’t escape. And while “The Educated Fool” and “Como Estais Amigos” were reflective and thoughtful, “Don’t Look to the Eyes of a Stranger” revealed that Harris was getting increasingly stodgy, given as it was to slightly grumpy old man musings that would reappear on and off over the next several Maiden records. Perhaps he thought the abrupt conclusion added a twist, but mostly it sounded like he didn’t know how to finish the song.

Even with this, when separated from the background and context surrounding it Virtual XI felt vigorous and distinctly Maiden, for better and for worse. And it is worth noting that the original version of the apparently deathless “The Clansman” was arguably sung with more brio than Bruce’s more theatrical spin on subsequent tours. “The Clansman” was actually a bit of a red herring: it was the tune that most deliberately recalled ‘80s Iron Maiden (which is certainly why it remains embraced by both the band and its fans), but it also played things safe in a way that the other tracks didn’t. And that was ultimately the double-edged sword that truly undid the album- fans so often complained about Maiden being overly set in their ways, but when they gamely tried to change things up and broaden their template a bit, everyone tore it apart except for the one where they did exactly what everyone expected. And with that, it was all too easy to blame the new singer for ruining everything, even though almost none of the decisions were made by him.

Virtual XI wasn’t the album anyone really wanted, nor was it the record it could have and should have been. But the album’s problems lay squarely on the shoulders of Steve Harris, and in its better moments, of which there were quite a few, it had a spark and a verve that made it a much better listen than it gets credit for.

You know, you can say the same about Kreator's so called "experimental phase".

There are really, but really astonishingly good sounds and Renewal and Endorama are very great albums.

But they were slammed back and forth until they returned to the same old "thrash-until-death-tormentor" kinda style.

Go figure.